Decades Later, the Truth Behind a Grisly Mass Murder in El Salvador

In the pallid light of dawn on December 3, 1980, a dairyman named Guadalupe Gómez trudged down a lonely dirt road near the village of Santiago Nonualco, El Salvador, off to milk his employer’s cows. A few hundred yards from the home of a comandante of the paramilitary civil defense forces, he was stopped in his tracks by the sight of four bodies sprawled by the roadside.

Mutilated corpses were not an uncommon sight around Santiago, one of the most conflictive corners of a violent country. But these bodies were different. They were light-skinned women, apparently foreigners. All four had been shot in the head. Later forensic examination, slipshod by American standards, suggested that at least three were raped.

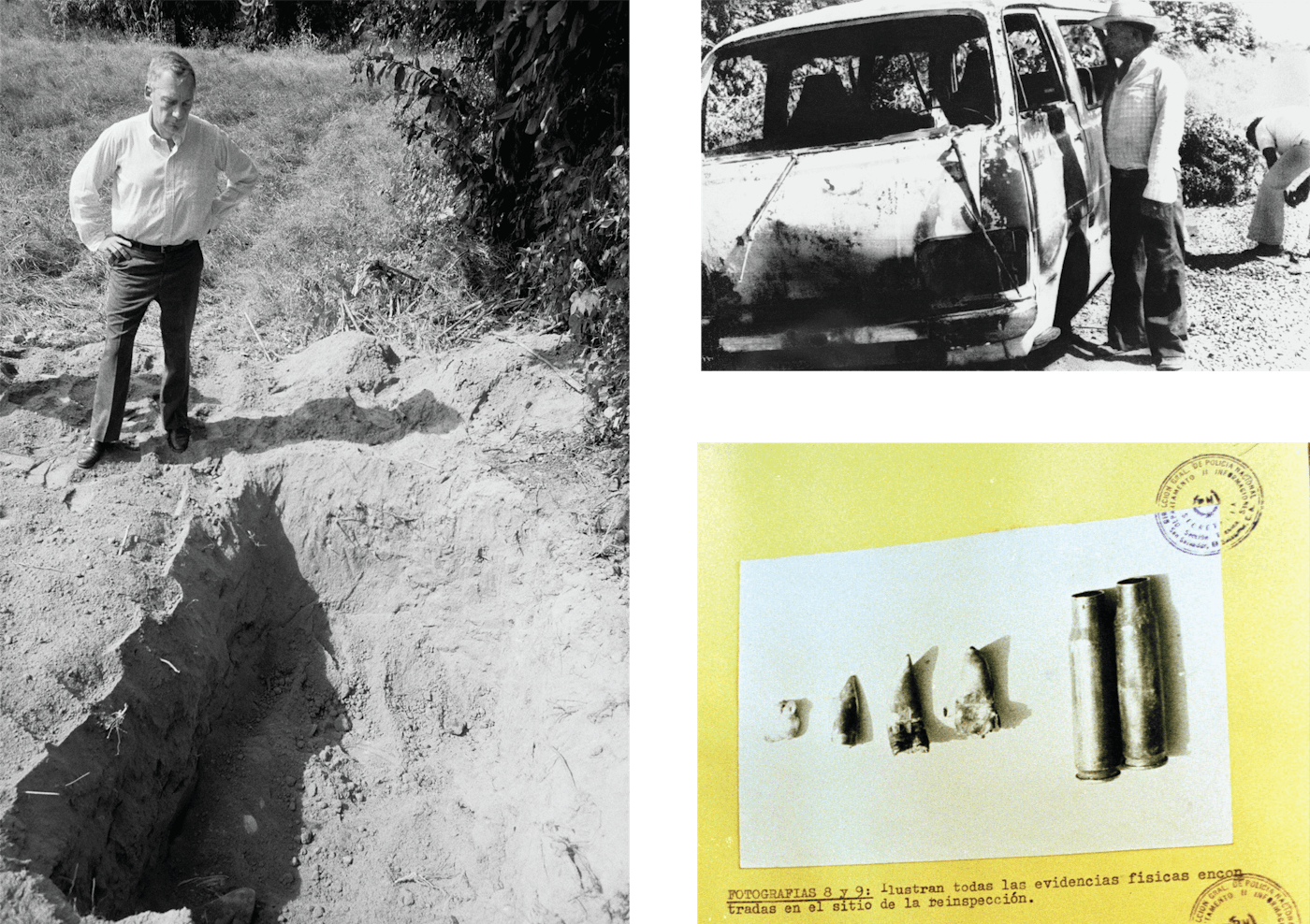

Later that day, they were buried in a shallow grave on orders from the national guard, whose operations here in the department of La Paz—like those of the regular army, the police, and paramilitary forces—came under the command of Lt. Col. Oscar Edgardo Casanova Véjar, a Chilean-trained intelligence officer based in the nearby town of Zacatecoluca and much admired by the Pentagon.

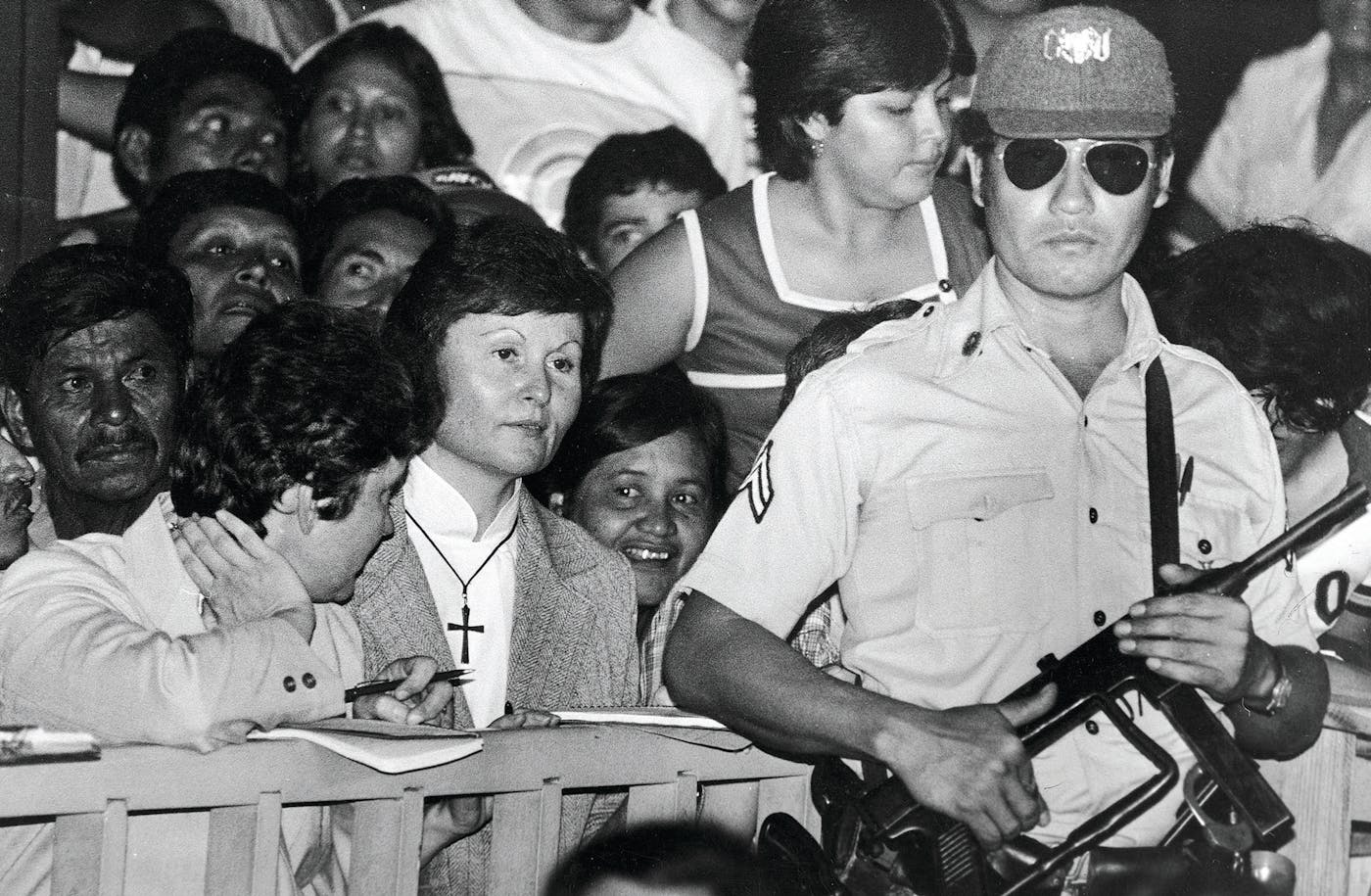

The following morning, the bodies were exhumed in the presence of U.S. Ambassador Robert White. Ita Ford, 40, and Maura Clarke, 49, were Maryknoll sisters who had worked in the mountainous department of Chalatenango, caring for the needs of refugees fleeing the first great rural massacre of the civil war that lasted from 1979 to 1992. Clarke had arrived only recently from Nicaragua, replacing Carla Piette, who had previously served with Ford in Chile and had drowned in a flash flood in August. The sisters’ work had subjected them to frequent threats, including from Defense Minister Gen. José Guillermo García.

Dorothy Kazel, 41, an Ursuline sister, and Jean Donovan, a 27-year-old lay missioner, were attached to the Cleveland diocesan mission in the grubby Pacific port town of La Libertad, overseen by an energetic young priest named Paul Schindler, who identified the bodies. They had a second base of operations in the nearby small town of Zaragoza, where they set up a shelter for women, children, and orphans escaping the violence in Chalatenango.

The four women, who worked closely together, were guided by an emergent principle in the Roman Catholic Church known as the “preferential option for the poor,” and they were fully aware of the risks this entailed. In 1980, El Salvador’s year of madness, collecting food, medicine, and clothing for refugees, telling a mother that the death of her baby was not the will of God, mourning the death squad murder of a catechist, distributing pamphlets with the archbishop’s latest sermon: Any of these things could label you a “subversive,” and that could be tantamount to a death sentence.

The women had agreed to meet on the evening of December 2, and Kazel and Donovan made the 20-mile drive from La Libertad to the newly opened international airport to pick up Ford and Clarke, who were flying in from the Maryknolls’ annual regional assembly in Nicaragua. Their flight touched down at 6:56 p.m. Kazel and Donovan entered the terminal to greet them, and all four vanished into the humid tropical darkness.

It took three-and-a-half years for the churchwomen’s killers, five low-ranking members of the national guard, to be brought to trial, and the future course of the war pivoted on their conviction, which came in May 1984. But no one else was ever held accountable. “The issue of who ordered the murders was a key question for us from day one,” said Jeff Smith, who was the State Department’s top lawyer on the case. “It was always hard for me to believe that these guys acted on their own initiative.”

With the evidence available to Smith at the time, it was impossible to prove otherwise. But as any cold-case detective knows, the shape of an unsolved puzzle can shift with the passage of time. Blow the dust off old files, and they shake loose new clues. Go back over witness testimonies, and previously unnoticed discrepancies emerge. Well-informed sources come out of the woodwork, sometimes because advancing age allows them to speak more freely, and sometimes to unburden a troubled conscience. Long-classified official documents can be forced into the light, and critical evidence long presumed lost or destroyed can even be unearthed decades later.

In this particular cold case, it is the secret recording of a conversation between the commander of the unit who murdered the women, a national guard sergeant named Luis Antonio Colindres Alemán, and a member of the inner circle of El Salvador’s notorious right-wing death squads.

The tape proves that Colindres Alemán killed the women only after receiving instructions from a superior officer and in collusion with a second security force, answering to multiple chains of command that reached to senior levels of the Salvadoran military and a clique of officers whose excesses were tolerated and shielded from scrutiny by U.S. officials for the sake of winning a civil war against leftist insurgents whose stakes were defined in existential terms. Hold back the red tide in Central America, Ronald Reagan famously warned, or Soviet tanks would soon be rumbling across the Texas border.

Why El Salvador?

It’s strange now to think back on those times, when tiny, dirt-poor El Salvador felt like the center of the geopolitical universe. In July 1979, the leftist Sandinistas had seized power in Nicaragua; three months later, a reform-minded military-civilian junta ousted the latest in El Salvador’s long parade of uniformed dictators.

For most of us who went to Central America as fledgling reporters, the war became personal. We gravitated to church workers as a source of reliable information. Sources became friends, and friends became victims of the carnage. For me, the first was Attorney General Mario Zamora, a Christian Democrat, gunned down in February 1980 after being denounced by Roberto D’Aubuisson, the hyperkinetic national guard intelligence officer who was the driving force behind the death squads. The last was Father Ignacio Ellacuría, the brilliant, cerebral rector of the University of Central America, and the most senior of six Jesuit priests murdered there in November 1989, along with a housekeeper and her teenage daughter.

Yet in all that ceaseless tide of atrocities, the churchwomen’s case always stood apart, with public and congressional outrage at the crime further inflamed by the trash talk from senior members of the incoming Reagan administration. U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick declaring that they were “not just nuns…. They were political activists on behalf of the Frente”—the Marxist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or FMLN. Secretary of State Alexander Haig insinuating that they might have been killed in an exchange of fire while running a roadblock.

Piecing together the full story of the churchwomen’s murders matters not only because it sheds dramatic new light on a deal made with the devil at a particularly ugly moment in a half-forgotten conflict. It’s also a parable of the dark moral compromises made when we become entangled in faraway places that engage our attention only in those rare moments when they’re seen as a threat to our national security. And there’s more: The case of the murdered churchwomen raises the enduring question of whether, in such moments of crisis, all parts of our government sing from the same hymn sheet, or whether the honest efforts of some can be sabotaged by the secretive maneuverings of others.

The National Police Take Charge

On the morning of December 3, Father Paul Schindler telephoned the U.S. Embassy’s consul general, Pat Lasbury, herself a former nun, to report the women’s disappearance. Lasbury immediately called the acting deputy chief of the national police, a 40-year-old major named Domingo Monterrosa, who was also head of the police academy, the Escuela de Policía. A pugnacious, charismatic paratrooper, with the features of a campesino, Monterrosa was a soldier’s soldier, a natural leader. But what was a man like that doing running a police academy? This was just one small instance of what might politely be called the idiosyncrasies of the Salvadoran armed forces.

The U.S. military was legally barred from working with domestic police forces, but the distinction was meaningless in practice, since their upper echelons were almost entirely staffed by regular army officers. The Pentagon knew most of these men quite well, having talent-spotted them at their graduation ceremonies from the military academy and trained them at the U.S. Army School of the Americas in Panama before they morphed into police officers. That was where Monterrosa had learned the skills of parachute rigging, D’Aubuisson had studied communications, and Roberto Staben, one of his closest associates, took classes in military intelligence. “The training didn’t stop them being thugs,” said Terry Karl, a Stanford professor emeritus and expert on the Salvadoran military. “It just made them better thugs.”

Later that day, Lasbury reached Monterrosa’s boss in the national police, Col. Carlos Reynaldo López Nuila. A military lawyer educated in Franco’s Spain, whose father was a Christian Democrat, he cut a bland and reassuring figure, unlike many other senior officers. That image was useful to the Reagan administration’s assiduous promotion of the national police as El Salvador’s “clean” security force, in contrast to the theatrical brutalities of the national guard and the treasury police, pigs on which it was harder to put lipstick.

In fact, the work of the national police in 1980 bore little resemblance to what Americans think of as routine policing. Its main job was to suppress “subversion,” and it housed what was probably the best organized and the most secretive of all the military death squads, its victims often abducted under cover of darkness and spirited away to clandestine prisons for interrogation, torture, and execution.

There was a rough division of labor among the three security forces. The national guard took savage care of dissent in the rural areas, the smaller treasury police had a more free-floating role, while the national police focused on urban civil society—labor unions, students and educators, lawyers and judges, the Catholic Church, and church-based human rights organizations.

The national police death squad was commanded by Maj. Arístides Alfonso Márquez, an officer described in one CIA cable as “a very mean person, who is to be feared.” Head of police operations was Maj. Roberto Staben, who also served as executive officer of the cavalry regiment, a post that gave him responsibility for intelligence-gathering and operations in the area of La Libertad and Zaragoza, where the Cleveland women worked.

The section that Márquez ran, designated D-II, handled not only intelligence, much of it supplied by the CIA, but all criminal and political investigations. It was D-II, for example, that headed up the investigation into the murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero in 1980, abandoned after six weeks following an assassination attempt by a national police death squad against the judge assigned to the case. There would be a thorough investigation of the churchwomen’s disappearance, Col. López Nuila promised Pat Lasbury. He entrusted it to Maj. Márquez.

The Security Forces and the CIA

Márquez and Staben had been in the same class, or tanda, at the military academy, graduating together in 1966. With 45 members, it was a particularly large and influential class, known as the tandona—the big tanda—or the sinfónica, because it was big enough to form a symphony orchestra. American military advisers in El Salvador were confounded by the tanda system, which bound each class together in a Mafia-like culture of mutual protection and collective complicity. Every officer, whether incompetent, corrupt, a drunk, a rapist, or a murderer, knew his classmates would always have his back, and as a group they rose through the ranks in lockstep, promotions coming like the regular clicks of a taxi meter. The top graduate in 1966, marked out for future high office, was René Emilio Ponce, who joined the treasury police before becoming an important member of the national police death squad.

Hard-liners like Márquez, Staben, and Ponce made common cause with like-minded officers from other tandas, like D’Aubuisson, Monterrosa, and the brutal chief of national guard intelligence, Mario Denis Morán, all from the Class of 1963. They in turn cultivated a cadre of younger acolytes, like Capt. Rafael López Dávila and Capt. José Alfredo Jiménez Moreno, both of national police intelligence. Each of these officers, I discovered, had played a part in the story of the churchwomen. Not only that, but the same cast of characters formed a through line connecting the murders to all the other worst atrocities of the war—the assassination of Archbishop Romero; the El Mozote massacre in December 1981, and finally the 1989 slaughter of the Jesuits.

The CIA played down the influence of the extremists, describing them as “a small clique of junior and middle-grade officers.” Technically true, but it was never a numbers game. What mattered were the ruthless measures they took to eradicate “subversives” and sideline the reformist officers who had led the 1979 coup. If pushed too hard on human rights, they would threaten rebellion, confident that the high command would close ranks in the name of military unity, and the United States would shy away from worsening divisions that risked undermining the war effort. Ultimately, they knew they could count on the protection of their political godfather, Col. Nicolás Carranza, the vice minister of defense and public security, who had overall command of the three internal security forces. Carranza also happened to be the CIA’s principal asset in El Salvador, paid $90,000 a year for his services.

With its undisguised contempt for Jimmy Carter’s human rights policy, the Reagan administration is often seen in El Salvador as making a sharp break from its predecessor. But it was more like a radical evolution, because the core dilemma for U.S. policymakers was baked in from the start.

Right after the 1979 coup, Carter issued a presidential finding instructing the CIA to support “moderate elements” and encourage “needed political, economic, and social reforms,” while at the same time providing “training and assistance to the intelligence and security forces of El Salvador to enable them to deal effectively with terrorism.” But these goals were incompatible, because those forces were the stronghold of officers most virulently opposed to reform. The churchwomen’s case lay at the heart of the tortured effort to square this circle.

Feeling betrayed by their traditional ally, the Salvadorans turned to more reliable friends. D’Aubuisson and Monterrosa went to Taiwan for training at the Beitou Political Warfare College, and D’Aubuisson sought help from the military regimes in Argentina and Guatemala. Above all, they looked to Chile, where Gen. Augusto Pinochet and his fearsome secret police, the DINA—which had kept a close eye on the Maryknoll sisters working in the shantytowns of Santiago—were an inspiration to right-wing extremists throughout Latin America. Shortly before the coup, Carranza’s predecessor, Gen. Eduardo Iraheta, flew to Santiago to meet with the dictator. His specific request: aid to upgrade El Salvador’s police academy, as a pivotal institution in the fight against “subversion.”

Soon after his inauguration, Reagan dispatched a special envoy to Santiago—former CIA Deputy Director Gen. Vernon Walters, who had helped to set up the DINA after the Pinochet coup. “We met as old friends,” he wrote after conferring with the dictator, in an “eyes-only” message to Haig. “Briefed him on the Salvadoran situation. He offered full support and said he would do anything we wanted to help us.”

The upgrade of the police academy was soon underway, with an enhanced capacity to conduct field operations. Its new commander would be Maj. Domingo Monterrosa, with young Capt. Jiménez Moreno as his deputy.

“Killer” Speaks

In July 1980, a junior political officer named Carl Gettinger arrived in the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador. Just 25, he was a Californian with a shock of black hair and a thick beard. “I looked like Che Guevara,” he told me, “and the military guys and the right-wing ladies who worked downstairs were convinced I was a commie.”

At the recommendation of the head of the U.S. Military Group, Col. Eldon Cummings, Gettinger cultivated a relationship with a young national guard officer whose father and brother had been assassinated by leftists. I identified him from confidential Salvadoran military records as Lt. Carlos Wilfredo Merino, but around the embassy people called him “Killer.” He was a brutal and volatile man prone to black rages, who claimed to have taken part in the assassination plot against Archbishop Romero. And yet, Gettinger said, “Killer was an ideal source. He had great connections, but he still had a shred of moral conscience.”

On November 26, the eve of Thanksgiving, Ambassador White read the traditional holiday proclamation at the American-founded Union Church, where Consul Pat Lasbury introduced Gettinger to Dorothy Kazel and Jean Donovan. Meeting them was a brief respite from the prevailing atmosphere of fear, Gettinger said. “I talked to them for about 10 minutes, I guess. Jean said there was a lot more she wanted to tell me about what was happening in La Libertad, and we agreed to meet again. But six days later she was dead.” On Thanksgiving Day, the terror escalated further, when combined security forces, acting on Carranza’s orders, raided a Jesuit high school and abducted, tortured, and executed six civilian leaders of the opposition Revolutionary Democratic Front, or FDR.

By the time of Reagan’s inauguration, White had been fired, and there was a four-month hiatus before the arrival of his replacement, a cigar-chewing cold warrior named Deane Hinton. Returning from a spell of home leave in late January, Gettinger was shocked by the lack of progress on the churchwomen’s case. The head of an official investigation, Col. Roberto Monterrosa—Domingo’s cousin—later candidly admitted that he ruled out any possibility of military involvement, since this would have caused political problems. A separate national guard investigation, assisted by two of Márquez’s police detectives, was going nowhere. So Gettinger went freelance. “I reached out to Killer again to see if he could help,” he said. “He really liked the idea. Spying and conspiracy can be a blast.”

After a whispered phone call and a risky clandestine meeting, Killer gave Gettinger a name: Colindres Alemán, commander of the 25-man national guard detachment at the airport. Killer knew Colindres Alemán and agreed to meet him wearing a concealed microcassette recorder. The highly classified tape came to be known as the “Special Embassy Evidence.” It was recorded in a moving car, much of it was unintelligible, and Gettinger, despite his fluent Spanish, could often only guess at what was being said. But Colindres Alemán named several others who were with him on the night of the killings and described a clumsy cover-up: guardsmen transferred to other posts, weapons switched. There was a murky reference to “some police,” but Gettinger concluded that Colindres Alemán had acted alone, driven by his personal brutality.

In September, Hinton asked Gettinger to review the dossier from the perfunctory national guard investigation. It was worthless, he reported, in a long memo summarizing every item in the file. Among these were “seventeen National Police (PN) documents which reflect its investigative efforts immediately after the December murders,” but these “delivered very little ground not covered elsewhere.”

In fact, according to a declassified CIA cable, the police investigator, Detective Inspector Saúl Tadeo Salazar Ardón, was the day-to-day commander of the national police death squad. His reports, prepared on orders from Márquez, a close personal friend, were the first building blocks in an official narrative of what happened on the night of December 2, starting with the testimony of the four paramilitary guards posted near the grave site.

Salazar also interviewed Father Paul Schindler, who had frequent run-ins with the national police. “It was always the police who came after my boys,” Schindler told me over lunch in the leafy garden of his parish house in La Libertad, citing the murder that summer of his sacristan, a good friend of Jean Donovan’s. “We always knew [the death squads] were here because they always parked their jeep in front of the national police headquarters. So everybody knew—don’t go out because the death squads were here.”

The inspector had been courteous, Schindler said. When I told him that he was a death squad commander, he smiled. “They were very hypocritical.”

Seventeen national police documents. The number nagged at me, because I’d put together my own hefty file on the police investigation, and it contained more than 20. Gettinger hadn’t seen all of them, and one proved to be the thread that began, once pulled, to unravel the larger story.

It was a chance discovery. I’d been looking to find out more about a Maj. José Emilio Chávez Cáceres, another member of the tandona, head of national police logistics at the time of the murders. But I turned up another Chávez Cáceres—his younger brother, Mauricio, a police lieutenant. A detailed police log identified him as commander of a surveillance operation at the airport on December 2.

Such an operation wasn’t in itself surprising. The country was on high alert, with the funerals of the murdered civilian leaders scheduled for the next day and visitors flooding in to pay their respects. The CIA believed that the event would trigger a long-anticipated “final offensive” by the FMLN, and stringent new immigration controls emphasized heightened scrutiny of air travel, especially arrivals from Nicaragua.

But the real significance of the police log was a note saying that young Lt. Chávez Cáceres was assigned to the police academy, where he took his orders from Maj. Domingo Monterrosa and Capt. Jiménez Moreno.

That wasn’t all. At 5:30 that afternoon, the log revealed, as Kazel and Donovan waited for the Maryknoll sisters to arrive from Managua, Chávez Cáceres’s units had rendezvoused at the airport with three national police vehicles from La Libertad. An embassy driver had actually seen those vehicles parked outside the terminal building, he mentioned later to Consul Pat Lasbury, which struck him as odd, since the airport was outside their jurisdiction. But no one had ever connected these dots.

The Atlacatl “Mobile Killing Unit”

Declassified cable traffic shows that State Department officials generally made a diligent effort to get at the truth, and especially to explore the fragmentary references to the police in Gettinger’s secret tape. The same was not true, however, of every agency of the federal government.

Even before the murders, Ambassador White had been demanding the removal of Col. Nicolás Carranza, the CIA’s main asset and overall commander of the security forces. Instead, immediately after the killings, he was given a plum intelligence post as head of the state telecommunications agency, ANTEL. Lt. Col. Casanova Véjar, who had commanded security operations in Zacatecoluca, was at the same time promoted to chief of intelligence for the armed forces general staff and subsequently named to a high-level U.S.-Salvadoran military planning group. As the long-awaited FMLN offensive fizzled and the war shifted from the cities to the mountains, the army created the first in a string of new rapid reaction infantry battalions. Named for a mythic sixteenth-century warrior, Atlacatl, it would be commanded by Domingo Monterrosa. He took Jiménez Moreno with him from the police academy, as head of the new battalion’s reconnaissance company.

Once Gettinger’s undercover informant had identified the churchwomen’s killers, the State Department pressed for a new investigation that would lay the groundwork for trial in a civilian court. Ambassador Hinton asked if Gettinger had any suggestions for officers to staff it. Despite being unfamiliar with the police, he mentioned Monterrosa. “I guess he must have come to mind as someone with some semblance of integrity, the best of a bad lot,” he told me.

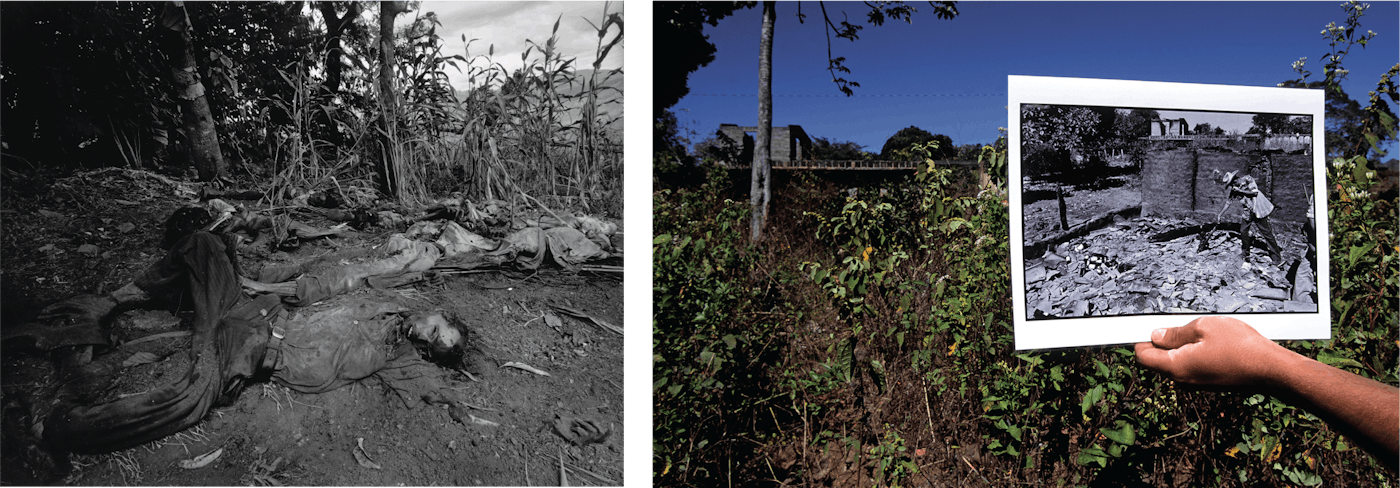

But Monterrosa, another embassy official pointed out, would be “difficult to get because he has important position with Atlacatl Battalion.” Indeed he did. On December 10, 1981, the day after this note was written, the Atlacatl launched a sweep around the village of El Mozote. By the time it was over, almost 1,000 people had been slaughtered, most of them women and children, the worst massacre in twentieth-century Latin American history.

Greg Walker, a retired Special Forces officer who trained Salvadoran troops, describes the Atlacatl as a “mobile killing unit,” akin to Himmler’s Einsatzgruppen in Eastern Europe. He also believes that Monterrosa had been a CIA asset. That assertion needed a more authoritative source, so I called David Morris, a former Army captain who headed the team that trained the Atlacatl in early 1981. Yes, he readily acknowledged, Monterrosa, whom he knew well, had been recruited as an agency asset, probably sometime in the late 1970s. I asked how he could be sure. Because, he said, he’d moved from the Army to the CIA after training Salvadoran troops and had seen the documentation on Monterrosa.

Another Cover-Up

The new investigation would create a true record of the facts and lay the groundwork for a civilian trial. But in the end, it had a similar makeup to its predecessor: It was led by another national guard major, José Adolfo Medrano, assisted by one of Márquez’s police detectives. The military had now had the detainees in custody for seven months, time enough to carry out a careful exercise in damage control. Medrano limited his investigation to a 24-hour period on December 2 and 3, immediately before and after the murders, interviewing only members of the national guard and purported eyewitnesses. Finally, he extracted a full confession from one member of Colindres Alemán’s squad. Many years later, according to still-confidential internal documents I was able to examine from the United Nations Truth Commission, established at the end of the war, this guardsman would tell U.N. investigators that he was “coerced into confessing.” But it gave Medrano a seamless narrative, with a firewall around any hint of a larger operation, higher orders, or the involvement of other security forces.

Bringing members of the military before a civilian court was a perilous business. Dozens of judges and lawyers had been murdered by the death squads, and Judge Bernardo Rauda Murcia, assigned to the case in Zacatecoluca, was further boxed in by Salvadoran criminal procedure law: He had to bring charges within 72 hours or release the prisoners. So his case effectively rested on accepting Medrano’s version of what happened.

It was also a fraught moment for the Reagan administration. On January 27, 1982, the day before the president had to certify to Congress that El Salvador was making sustained progress on human rights, news had broken in The New York Times and The Washington Post of the horrific El Mozote massacre. But Reagan dismissed the reports as communist propaganda, and Assistant Secretary of State Thomas Enders, generally viewed as one of the administration’s moderates, testified before Congress on the certification on schedule.

The churchwomen’s families met with Enders shortly after that and presented a list of questions, which he referred to the embassy. Question 12: “Were there other police organizations represented at the airport on the evening of the killing?”

The response came back a month later, over Hinton’s signature: No. It was the only outright lie ever told to the families, but it went to the crux of the whole story.

The Witnesses Were Dead

For more than a year, further progress stalled, until, early in 1983, a long-festering factional dispute within the Salvadoran military erupted that would shape the course of the trial, and of the war. With presidential elections in El Salvador approaching the following spring, CIA Director William Casey was like a man straddling two rowboats that were drifting apart. The agency was providing intelligence to the security forces, which had the effect of empowering the death squads; yet it had to head off the risk of D’Aubuisson and his newly created party, ARENA, winning the presidency, which Congress would never stomach. Casey threaded the needle by covertly supporting D’Aubuisson’s Christian Democratic opponent, José Napoleón Duarte.

The Pentagon, meanwhile, faced its own dilemma. The Salvadoran army was losing ground on the battlefield, facing the explicit threat of losing U.S. military aid unless the churchwomen’s killers were convicted, and riven by internal conflicts. That April, under pressure from extreme rightist officers, Defense Minister García was replaced by the former head of the national guard, Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova. In June, Joseph (“Smokin’ Joe”) Stringham, a legendary veteran of the Special Forces in Vietnam, arrived to take command of the 55 American military trainers in El Salvador. The army was fighting a 9-to-5 war, he told me in an interview last May, and he set out to implant more aggressive tactics. At Stringham’s urging, Vides announced a new round of promotions based on talent, not nepotism.

This must have been tricky, I said, since the most effective field commanders were often the most brutal. Yes, Stringham agreed, “that’s a very reasonable thing to say.” When I asked which officers he’d most admired, it was clear that he didn’t choose them for their politics but for their combat skills. He singled out, for example, a lieutenant colonel named Miguel Méndez, who was known for his progressive political views, as well as René Emilio Ponce, leader of the tandona and member of the police death squad. But head and shoulders above the rest was Domingo Monterrosa, who was now given command of the eastern third of the country. “[Domingo] was a terrific guy, a very close friend,” Stringham said. “Of course, he was the initial commander of the Atlacatl. Violent? Yes. Excessively violent? I never talked to him about that, we just let it go, because I didn’t know about it firsthand.”

But most people associate him with the El Mozote massacre, I said.

“I don’t remember that specifically,” Stringham said. “So many of those things went on, on both sides.”

To break the endless logjam on the churchwomen’s case, Secretary of State George Shultz appointed an independent expert, former Federal Judge Harold E. Tyler, to review all the evidence. Shultz demanded full cooperation from all federal agencies, and State Department lawyer Jeff Smith worked closely with Tyler’s team. The problem, Smith said, was that their findings could only be as good as the material they were given to work with—which meant the testimony gathered by Maj. Medrano and Márquez’s detectives and replicated by Judge Rauda Murcia, and Gettinger’s “Special Embassy Evidence,” which sat locked away in a safe with all its riddles.

Gettinger told Smith that the tape’s technical deficiencies, the lack of corroborating evidence, and the lingering questions about the police “combine to limit its usefulness.” Besides, why struggle to decipher the inaudible passages since the evidence wouldn’t be admissible anyway?

Nevertheless, he asked Killer to take one more crack at it. He found him in an ugly mood, and after polishing off the better part of a bottle of whiskey, the lieutenant refused to go on, just as they reached the critical passage about what happened at the airport.

Embassy officials did their best to find out more, fretting that if the tape ever came to light without a satisfactory explanation to Congress of “the police angle” or the “lateral involvement” of a second security force, they wouldn’t “have a leg to stand on.”

Smith pressed the issue with the attorney general, the prosecutor, and the embassy’s legal adviser. “Méndez [the legal adviser] had been a boxer, and he was a tough character,” he recalled. “But the AG didn’t want to do anything. We met him late at night, and the man was terrified.” There was “absolutely no interest” in opening a can of worms about the police.

The only option that remained was to track down three material witnesses who might know more: two guardsmen who had been on duty in the airport parking lot and might have communicated with the police, and the corporal left in charge of the guard post when Colindres Alemán set off that night. Alas, the national guard reported, all three witnesses were dead: one in combat, one MIA, and one in a car crash. “Such things happened often in sensitive cases,” said Terry Karl, the Stanford expert on the Salvadoran military, “especially as they learned to make their cover-ups more sophisticated.”

Finally, Convictions

The FBI’s hands were largely tied, Smith said, “because until 1986 there was no federal statute making it a crime to murder an American citizen outside the U.S.” The bureau had collected fingerprints, run polygraphs, analyzed ballistics, but none of this was admissible in court. Its role was restricted to assisting the national police, which meant deferring to Márquez—now promoted to lieutenant colonel—who controlled the criminal investigation.

In late June, an FBI special agent arrived in San Salvador for a two-week visit. With the high command on notice that U.S. military aid hung in the balance, it was finally time to throw the five guardsmen to the wolves, and Márquez could not have been more cordial. The American and the Salvadorans peered through high-powered microscopes, test-fired bullets into an Olympic-size swimming pool, and in the end produced evidence that would stand up in court. The trip ended with a convivial social evening.

As for the CIA, with the death squads resurgent, Director Casey flew down to San Salvador to tell Col. Carranza to rein them in. Such distasteful tactics might have been effective in 1980, but they were now counterproductive.

The FBI’s intelligence division asked Casey to share with Judge Tyler all CIA documents relevant to the case, pointedly reminding him that Secretary Shultz expected full cooperation. The agency offered up 10 documents. Most were boilerplate, but four lengthy cables were almost entirely redacted, citing “the extreme sensitivity of the sources and methods by which the information was obtained.” Even the fragments that escaped the black Sharpie were classified secret, and the CIA insisted on prior review of Tyler’s report before it went to Congress. His associate, former Secretary of the Army Togo West, sent the packet straight back, with a frosty note saying it was useless.

Jeff Smith had no recollection of seeing any of this correspondence. “We told Congress and the families in good faith that we didn’t know who was ultimately responsible for the murders,” he said. “But if there was such knowledge at the time, and we were not told, I would be very angry. I can think of no legitimate reason why we should not have been given that information.”

“Presumably you had top-secret security clearance?” I asked.

“Oh, my clearance went much higher,” he replied, “what’s known as SCI, Special Compartmented Information, which gives you access to projects that are specially protected by codewords.”

Under the Freedom of Information Act, I requested expedited processing of the release of the most heavily redacted CIA documents, but my request was denied. Yet the documents volunteered by Casey weren’t the only issue, because I’d found many more secret CIA cables that were germane to the churchwomen’s case, all dated before the FBI’s request. The most significant of these was written in March 1983. It was a detailed analysis of the history, structure, leadership, and membership of the death squad that was run out of national police intelligence, dating back to 1979 and the assassination of Archbishop Romero. Márquez was its commander. Inspector Salazar, who had led the initial investigation into the women’s disappearance, ran day-to-day operations. Capt. Rafael López Dávila, Márquez’s deputy, oversaw a secret torture and execution center, a guarded compound near the airport, on the road from Zacatecoluca to La Libertad. René Emilio Ponce provided false documents and license plates for vehicles used by the death squad. Roberto D’Aubuisson sometimes selected the targets for assassination.

In December, Vice President George H.W. Bush traveled to El Salvador to read the riot act. Stringham had given him a list of eight military death squad leaders, which Bush handed to Vides, demanding their removal from their posts. The two most senior were Márquez and Denis Morán, head of national guard intelligence, who was now operating a new death squad in Zacatecoluca, where the trial of the churchwomen’s killers would be held.

El Salvador’s top commanders duly signed a pledge to eradicate the death squads, and Vides appointed a commission to investigate human rights abuses by the military. It was headed by a national guard intelligence officer, Capt. Ricardo Arango Macay—a veteran, along with D’Aubuisson, Staben, and Morán, of the White Warriors Union, a death squad that specialized in killing priests.

And CIA support for national police intelligence continued. In March 1984, López Dávila gave a young freelance reporter a tour of the revamped police files on suspected “subversives.” The intelligence came from the CIA, he explained. “[The Americans] receive information from everywhere in the world,” added Carranza. “It’s very helpful.”

And so, the churchwomen’s case limped its way to the finish line, and on May 24, 1984, Colindres Alemán and four others were convicted of aggravated homicide and sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment. The military had made an unavoidable but ultimately small sacrifice, and the firewall around senior officers and the police had held.

With the convictions secured, Congress immediately approved $62 million in emergency aid. That same day, a new set of military transfer orders went through. Carranza and Márquez were quietly sent abroad as military attachés, and Morán headed for Washington for further training at the Inter-American Defense College. There are times when coincidences of timing stretch credulity.

The Secrets of the Tape

Judge Tyler’s belief that Colindres Alemán acted without higher orders rested on the national guard-national police investigation and what Gettinger had gleaned from Killer’s secret tape.

Tyler had trusted in Maj. Medrano’s professionalism, and no doubt that was how he presented himself. Not all officers conformed to Gettinger’s stereotype of “uniformed thugs with blood dripping from their mouths.” But in fact, Medrano, trained in urban counterinsurgency at the School of the Americas, went on to become head of national guard intelligence. In 1986, he was identified by Salvadoran and U.S. intelligence officials as having himself been active in death squad operations.

But there were too many unexplained gaps in the recording, too many discrepancies in the evidence, too many dead witnesses. Only the tape could provide clearer answers, but it had never been declassified and had long since vanished. Last year, as I was working on this story, officials at the State Department and National Archives agreed to search for it, but they came up empty, and I assumed we’d reached a dead end.

Then, out of the blue, many months later, one of the officials called to say he’d found it. It had been reviewed, digitized, and approved for declassification.

With the help of state-of-the-art audio software, I spent five hours poring over the 19-minute recording, with three Salvadoran interpreters conferring until they agreed on every word, penetrating the local slang and the welter of obscenities, watching fascinated as multicolored bands of sound danced across the screen, filtering out background noise and unwanted frequencies, until it was possible to piece together the missing parts of the puzzle.

Perhaps the darkest irony of the tape was why Colindres Alemán trusted Killer enough to confide in him. They’d met in the fall of 1980 at the School of the Americas, attending a short-lived course—canceled by the Reagan administration—on human rights. I tracked down the class roster. Other than Killer, only a handful of officers had participated, but among them were López Dávila of police intelligence, and Chávez Cáceres of the police academy, who had commanded the stakeout of the airport.

The tape confirmed that Colindres Alemán had gone out to the parking lot to meet with the national police at the airport, who told him that the women were “subversives.” According to the confidential internal report of the U.N. Truth Commission, the national guard sergeant had driven to the nearby treasury police post at about the same time to alert them that an operation was imminent, possibly involving gunfire. So all three security forces under Carranza were now woven into the web of complicity.

After the Maryknoll sisters’ plane arrived from Managua, Colindres Alemán told Killer, he had met with an unnamed lieutenant stationed at a computer, part of the newly upgraded communications and intelligence facilities at the airport. The officer told Colindres Alemán that they were on their way to the funeral of the murdered FDR leaders and showed him correspondence they’d been carrying, destined for una mera—“a top woman,” in Salvadoran slang—in La Libertad. They were suspected, Colindres Alemán said, of “transporting weapons and I don’t know what else to a cantón over by Zaragoza,” where the Cleveland diocese had just opened its shelter for orphans fleeing the violence in Chalatenango.

Colindres Alemán said he would take care of the problem. Later, when he searched the women’s minivan, he told Killer, he found un vergón—a shitload—of what he called “propaganda.”

“And that’s how the job was done,” he went on. “We smoked them over by Santiago Nonualco.”

The naked brutality of Colindres Alemán’s language was enough to persuade Gettinger that the sergeant had acted alone.

Accusations by more senior military leaders that the churchwomen had been “subversives” bothered the embassy’s Marine attaché so much that he raised the issue in a confidential October 1983 cable to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, describing a conversation with a military source about the murders. The contents of the cable and its sloppy redactions point strongly to Roberto Staben, who had been in charge of intelligence and operations in La Libertad and Zaragoza. Now, newly promoted to command an elite battalion, he was about to embark on joint combat operations with Domingo Monterrosa’s Third Brigade.

The women had been “terrorists,” the officer said; it had just been a “simple wartime execution.” But what on earth justified that preposterous charge, the attaché asked. What were they supposed to have been taking to the guerrillas? “Messages, medicines, shoes, clothes, and that sort of thing,” the officer replied. The sort of things a humanitarian aid worker might be expected to take to a shelter for refugee orphans. These comments, the Marine concluded, “reveal again that a different mentality and a different logic exist in El Salvador which does indeed make effective communications between respective societies sometimes extremely difficult.” But it was a logic to which the United States, whatever its moral qualms, found itself wedded by the bottom-line goal of winning the war.

Judge Tyler’s version of what happened on the night of December 2, 1980, suggesting that Colindres Alemán had acted on his own initiative, has been passed down unchallenged in 40 years’ worth of books, articles, documentary films, and human rights reports. But that story falls apart once the secrets of Gettinger’s tape have yielded to today’s technologies. If the women were detained and searched at the airport, it corroborates an entirely different version of events, one that Paul Schindler had recounted to Tyler, who rejected it as a “red herring” simply because it conflicted with the story crafted by Maj. Medrano and the national police.

Schindler repeated it to me over our lunch at the parish house in La Libertad. He always took it for granted that the military had murdered the women, but after taking the bodies of Donovan and Kazel back to Cleveland for burial, his only concern was to be there for his parishioners, at a time when other priests were fleeing the terror. Some of those who flocked to his church to offer condolences worked at the airport. When the plane from Managua landed, the terminal was about to close for the night, and given the dangers of being out after dark, workers on the evening shift often slept over. “They saw all the passengers leave,” Schindler said, “apart from Dorothy and Jean, who were still waiting, until finally a couple of guys in uniform took them off to an inner room where Ita and Maura were already being held. That’s where they were detained. The rest is all nonsense.”

“No lowly sergeant in the national guard would have had the authority to interrogate suspects like the American nuns,” said Argentine lawyer and military expert Alfredo Forti, an investigator for the Truth Commission. “Only an intelligence officer could have done that, and it could only have been done following superior orders and in a secure location.”

That pointed clearly to a military training base called the Cuartel de Miraflores, which covered hundreds of acres of desolate scrubland and forest just a 10-minute drive from the airport and exactly matched the location of the guarded compound where, according to the CIA, Capt. López Dávila had run the national police’s secret torture and execution center. “Taking the women there was indeed the most logical scenario to reduce the risks in such a sensitive operation,” Forti said.

“Oh yes,” Paul Schindler said, as if it was obvious. “The Cuartel de Miraflores was the base for the death squads in that whole area.”

The Persistence of Memory

During that time of madness in El Salvador, we often heard talk of the “fog of war”—how hard it was to understand the military’s eccentric command structure. But the extremists were always a coherent clique, and once Gettinger’s tape and Schindler’s story were added to the mosaic of evidence, you could see clearly the roles that many of its leading members, colonels and majors, had played in the churchwomen’s case: Carranza, responsible for joint security force operations; Monterrosa, for the surveillance of the airport; Casanova Véjar, for all forces in the department of La Paz; Staben, for intelligence on the women’s work in Zaragoza; Márquez, for the criminal investigation. Over and above their brutality, all these officers had one thing in common—their close ties to U.S. intelligence.

What the leaders of the Salvadoran death squads and others of their kind invariably underestimate is the power and persistence of memory. Each year on December 2, religious communities around the world still gather to honor the four churchwomen on the anniversary of their deaths. Human rights experts like Terry Karl doggedly pursue war criminals in foreign courts.

For Jeff Smith, the top State Department lawyer on the case, what remains at stake four decades later is the integrity of U.S. foreign policy. “Beyond pressing for justice in El Salvador,” he said, “this was about fostering the broader principle of the rule of law.” Smith went on to serve as general counsel of the CIA during the Clinton administration, and the agency’s role in the affair touches a raw nerve. “This was such a significant case that it’s important to know what was redacted from those cables,” he said, “and whether everything the CIA knew was shared with Judge Tyler and other senior officials. So it would be appropriate for one or both of the intelligence oversight committees in Congress to request full access to those cables and any other documents relevant to the agency’s relationship with Salvadoran security forces.”

By the time the war ended in 1992, 75,000 Salvadorans were dead. Domingo Monterrosa’s Atlacatl Battalion left a trail of tears wherever it went. It was Atlacatl commandos who murdered the Jesuit priests in 1989, on orders from a cabal of colonels headed by René Emilio Ponce, leader of the tandona and an alumnus of the national police death squad. Roberto Staben’s name was often associated with El Playón, a volcanic lava field that was the most infamous of the death squads’ body dumps. He and José Alfredo Jiménez Moreno, Monterrosa’s old sidekick from the police academy and the Atlacatl, went on to operate a kidnapping ring that netted millions from rich businessmen.

Many are dead now. Monterrosa himself was assassinated in 1984 by a bomb placed in his helicopter. His subordinate, Lt. Chávez Cáceres, perished in a car crash in 1991—ironically, on the airport highway. Roberto D’Aubuisson died of cancer the following year, and Ponce of natural causes in 2011. Nicolás Carranza passed away peacefully in Memphis, Tennessee, in 2017, a naturalized U.S. citizen, a pillar of his local church. He said his only regret was having worked for the CIA. Arístides Márquez died in 2019, Vides in December 2023, and Casanova Véjar, his cousin, last July.

Others live out their golden years quietly in El Salvador, keeping in touch with old tanda-mates on Facebook, grumbling at efforts to reopen old cases like the massacre at El Mozote. As for Carl Gettinger’s informant, Lt. Merino, he was reportedly murdered by unknown assailants sometime in the 1990s. Common crime? A personal vendetta? Long-delayed retribution for his betrayal of the national guard? “All I know,” Gettinger said, “is that he would have gone out with guns blazing.”

Epilogue: The Long Tail of War

Paul Schindler, now 84, intends to spend the rest of his days in La Libertad; he’s already chosen his burial place. He took me to see the spartan upstairs room where Jean Donovan had slept, occupied now by a housekeeper. On a street behind the church, there is a colorful mural with portraits of the four women and Archbishop Romero. When a new mayor was elected a few years ago, a member of D’Aubuisson’s old ARENA party, he’d ordered it painted over. Schindler had it painted back again.

The coastal strip around the port, with its miles of golden beaches and booming breakers, is a tourist mecca these days. A new four-lane bypass leads to Surf City, site of the 2023 World Surfing Games. Beyond that is a place called El Mirador, where Schindler once found the decomposing remains of five death squad victims dumped at the foot of the cliffs. Today it’s just an idyllic, palm-fringed crescent of sand, encircled by resorts and Airbnb rentals.

In Santiago Nonualco, next to the chapel that was built where the women’s mangled bodies were found, villagers recently added a small white monument, decorated with sculpted angels, photographs of Ford, Clarke, Kazel, and Donovan, and the text of the Beatitudes in the Gospel of Matthew: “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.... Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.”

The Cuartel de Miraflores remains in occasional use today as an army training base. It still has a forbidding air, with a crude metal gate behind which a dirt track disappears into the dark subtropical forest. The road from there to Zacatecoluca is dotted with evangelical churches, simple one-room structures with a few cheap plastic chairs. One consequence of the war, said the bishop of Zacatecoluca, Elías Samuel Bolaños, is that much of his congregation has been lost to the Pentecostals, who offered a simple path to salvation and “attacked the church for its social engagement, its work with the poor.”

In 1980, there were 95,000 Salvadorans in the United States; when the war ended, there were over a million. Their exile communities nurtured vicious criminal gangs like Mara Salvatrucha, MS-13. Deported en masse in the 1990s and 2000s, these engulfed El Salvador in a new reign of terror. By 2015, the nation had the highest homicide rate in the world, generating a new exodus, stoking the nativist rhetoric of Donald Trump’s first election campaign.

The worst of the gang leaders were jammed into a maximum-security jail in Zacatecoluca, familiarly known as Zacatraz. Since then, the populist president, Nayib Bukele, has suspended many civil liberties, firing judges and opening the world’s largest prison, five miles from Zacatraz, with a capacity for 40,000 inmates, now including the alleged Venezuelan gang members sent there by the Trump administration. In a traumatized society, these draconian measures are wildly popular, and Bukele has become a star of the Trumpworld firmament, his inauguration for a second term last June attended by a group of MAGA luminaries that included Donald Trump Jr., Tucker Carlson, and Matt Gaetz. In February, in a post on X, Elon Musk applauded Bukele’s purge of the judiciary: “That is what it took to fix El Salvador. Same applies to America.”

“In a country where judges and lawyers were threatened and assassinated, we fought to bring to justice those who raped and murdered four courageous churchwomen,” said Jeff Smith. “And now Musk is praising Bukele’s attacks on the justice system. What are those women telling us from the shadows that we should do in our country today?”

Both the gangs and the Pentecostals had put down deep roots in places like Apopa, a downtrodden city on the road to Chalatenango. It was in Apopa that I found Sgt. Luis Antonio Colindres Alemán. He was granted early release in 1998, part of a program to relieve prison overcrowding. He’d been a model inmate, the warden said, keeping to himself, making furniture to earn a little money. Freed from jail, he made no secret of his bitterness at being scapegoated. “Why were we singled out?” he asked local reporters. “Why us? What was the purpose behind this?”

Today he is the pastor of a small Pentecostal church in Apopa, an affiliate of the Assemblies of God.

“It’s true that I experienced situations of extreme violence,” he said when I asked him about the war. “The international situation in those days was very complicated.” When I mentioned his service in the national guard, he hesitated. “Call me later and we can talk more,” he said at last. I sent him several follow-up messages, but he never responded, and in truth, I hadn’t expected him to.

El Salvador had never made peace with its past. But could an individual like Colindres Alemán, capable of such barbarity, find personal redemption? Maryknoll Sister Helene O’Sullivan, who had attended the trial of the guardsmen with Carl Gettinger, didn’t find this a useful question. “Instead of looking at him, we Americans need to look at ourselves,” she said. “The violence, the refugees, the deportations, the gangs, the evangelicals—the United States government created all this and left Salvadorans with a twisted society. If we question our own actions, perhaps we can make a difference. As for Colindres Alemán, that’s between him and his God.”