Joan Didion, Eve Babitz, and the Biographer Who Missed the Point

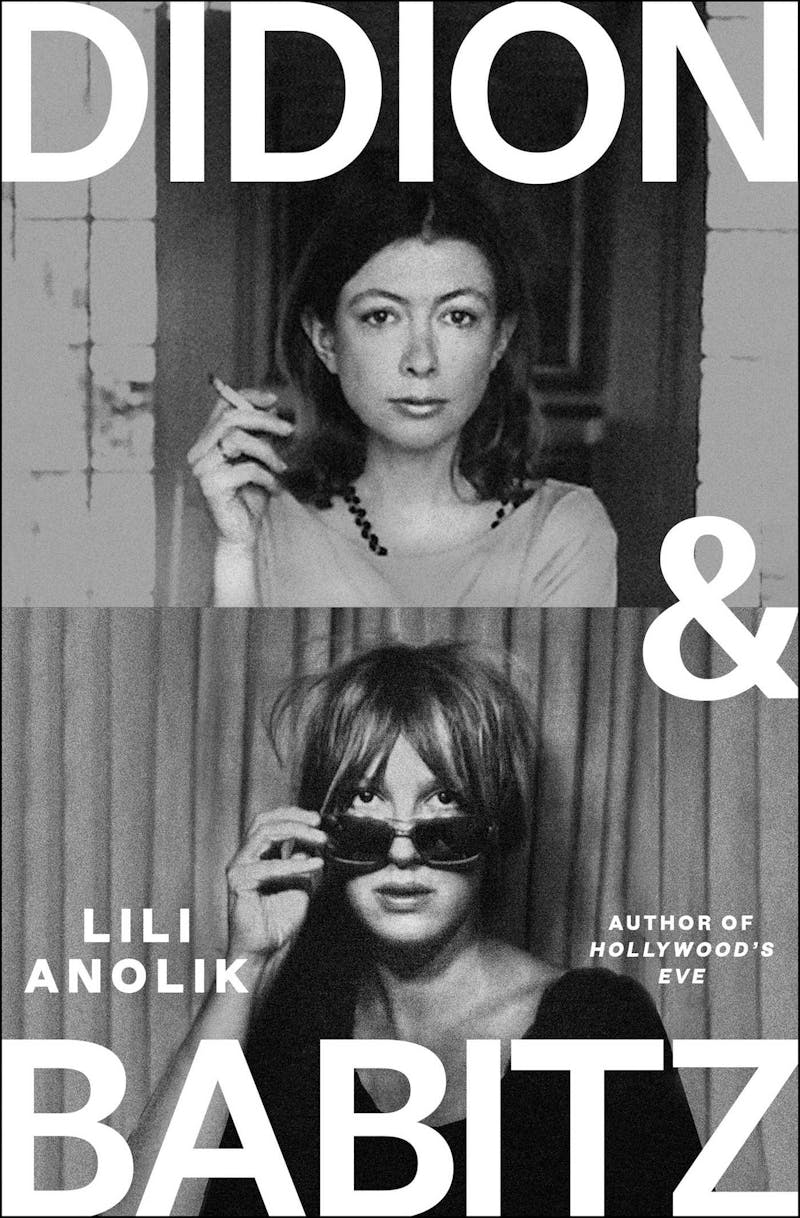

In a 1939 essay, the critic Philip Rahv argued that there have been two main types in American literature: the solemn and semi-clerical, which he associates with Henry James, and the exuberant, open-air lowlife embodied in Walt Whitman. Between them, James and Whitman represent the distinction between “life conceived as a discipline” and “life conceived as an opportunity.” Knowingly or not, Lili Anolik’s dual biography, Didion & Babitz, endeavors to revive Rahv’s opposition, this time for the ladies. Her protagonists, Joan Didion and the lesser-known writer-party girl Eve Babitz, met in Los Angeles in 1967, and were friends for perhaps seven years with, according to Anolik, lasting effects on American letters and culture.

In Anolik’s update on the Rahvian opposites, Didion was manufactured and careerist, as deliberate a creation as a character in one of her books, leading a life of dull industry while leeching off Babitz’s vitality. The exuberant Eve, who never passed up a drug, a bed partner, or an adventure, couldn’t be bothered with reputation. A messy free spirit, “an artist in the grand and romantic style,” she was original and profound and for real. Didion had a chaste presence and only two lovers in her life (by Anolik’s count); Babitz had “sexual valor.”

Frog-marching her subjects in a Jungian direction, Anolik declares them each other’s “shadow selves”: Each was what the other “feared becoming and longed to become.” Joan, who stayed so carefully within her own limits, would have been “dazzled, excited, maybe even a little intimidated” by Eve’s freedoms, Anolik imagines, envying and looking up to her. They’re “two halves of American womanhood,” and you can’t read one without the other. Didion without Babitz “is the sun without the moon.”

Didion’s well-known contempt for formulaic language of this sort (celestial and otherwise) remains a standard to emulate. All the same, disliking Didion has long felt like my shameful literary secret: Her stylistic tics set my teeth on edge, I find the novels sententious, the sweeping pronouncements of the essays frequently hollow. Perhaps unreasonably, I never feel more Jewish than when someone’s going on about how many generations back they can trace their westward-trekking forebears, making Didion’s confident ancestry and her confident decrees about American rot and unraveling sound like land grabs in different guises. (Maybe the nativist-tinged preoccupation with bloodlines and decline hits the ear more jarringly in MAGA times.)

We all have our Didions, and I don’t expect mine is yours. Mine also isn’t Anolik’s, whose vitriol toward her is so mean-spirited as to appear, at times, unhinged. Dead writers are public property, of course, available to all as free punching bags and cudgels. Yet Didion & Babitz gets into the desecration business with a peculiar agenda. Anolik has made a career out of rediscovering Eve Babitz, which culminated in her well-received 2019 biography, Hollywood’s Eve (some portion of which she recycles in the present book, she acknowledges), and apparently operates from the assumption that there’s only room for one revered female literary icon at a time. Didion needs to be dislodged because Babitz was the sexier and more improvisatory of the two—even if only one of her books (Slow Days, Fast Company) was, in Anolik’s own estimation, really great.

There are better reasons to want to dethrone Didion, among them her malign influence on a younger generation of confessional essayists—pridefully nurturing their neuroses and ailments like a crop of hothouse tomatoes, pointing their special social antennae into the wind and issuing Didionesque pronouncements about the national mood. “We live in anxious times,” they intone, when what they mean is that they are anxious—yet also sufficiently hearty to eviscerate one another’s confessional essay collections with competitively energetic daggers of prose. Anolik isn’t wrong about the power of frailty; the problem is that, however much she mauls Didion and romanticizes Babitz, their accomplishments simply aren’t equal.

Anolik was a fledgling writer when she tracked Eve Babitz down in 2012 and persuaded her to be interviewed for a Vanity Fair piece, though even by that point Babitz, who died in 2021, was in awful shape, speaking in disconnected sentences Anolik had to learn to decode. Nine years younger than Didion, she’d been a captivatingly self-entranced whirlwind and, famously, the large-breasted nude woman playing chess with Marcel Duchamp in the iconic 1963 Julian Wasser photo. She’d wanted to be an artist herself, flitting through mediums until ending as a writer. She was brash and funny (“Look at these breasts” she’d say to people, “These breasts have conquered the world”), had sex with a lot of famous men (and the occasional famous woman), and was good at making people want to give her things—professional favors, rent, grocery money, jewelry, a car. In the words of art critic Dave Hickey, she had “erotic charisma.”

Anolik lionizes Babitz’s bravura, recklessness, and capacity for pleasure: “Playing the courtesan-groupie was how Eve filled herself with the spirit of her time and place.” Her Vanity Fair article led to Babitz’s books being reissued; cool girls posted selfies featuring their covers; TV came calling, as Anolik recounts, taking a victory lap. Their fortunes now rise and fall as one, but she’d long felt they were in a story together, a romance: herself the besotted lover, Babitz testing her devotion. She knows saying this makes her sound deluded, but she also doesn’t care.

The new book was occasioned by Anolik discovering, among Babitz’s posthumous papers, an angry unsent 1972 letter from Babitz to Didion, prompted by Didion’s infamous essay on the women’s movement (“To make an omelette you need not only those broken eggs but someone ‘oppressed’ to break them…”). Accusing Didion of failing to understand herself, the female condition, or her own marriage, Babitz indicts Joan’s refusal to read Virginia Woolf, and her habit of preferring to be with the boys while reaping the privileges of being small and conventionally feminine. The balance of power between Didion and her less-successful husband, John Gregory Dunne, would have collapsed long ago, fulminates Babitz, if he didn’t regard her as a child, making her fame easier for him to take.

Didion’s feminism essay is indeed politically obtuse (with a few punchy lines), but she didn’t put much faith in social progress generally. She did, however, despite her feminist failings, mentor and promote Babitz, leading to writing gigs at Rolling Stone and contacts with book editors. She even attempted, along with Dunne, the labor-intensive task of editing Babitz’s unwieldy Eve’s Hollywood manuscript, until Babitz got defensive and announced scornfully around town that she’d “fired” Didion, going on to parody her in the book as “Lady Dana Wreaths,” a fashionable writer with a ridiculous life who’d tried to edit Babitz, but whose own books were “brutally depressing.”

To Anolik, the unsent letter is “a lovers’ quarrel”—“recriminations and resentments hurled like thunderbolts, the flashes of rage, despair, impatience, contempt.” But they weren’t lovers: It’s only the structure of Anolik’s book that requires forcing them into a dyad. It’s also not evident that the volatile Babitz’s feelings about the taciturn Didion were particularly reciprocated—Didion wasn’t writing Babitz angry unsent letters, or dedicating books to her (Eve’s Hollywood includes a dedication to the Didion-Dunnes), or basing characters on her. Nevertheless, we’re told their relationship was “as profound and rare as true love, as profound and rare as true hate.” If this seems overblown, well yes, it is—to such an extent that Anolik, who positions herself as the third lover in the story (“a Peeping Tom peering through the keyhole”), becomes an increasingly unreliable narrator of it.

Anolik wants Babitz, whom she reveres “with a fan’s unreasoning abandon,” to replace Didion as a literary icon, thus she hurls a lot of scattershot character indictments at Didion, largely about her ambition, which is a weird thing for one woman writer to indict in another. Among Didion’s other feminine failures: She only pretended to take pleasure in domestic life, was frail yet also bold (“a predator who passed herself off as prey”), was withdrawn but had a need to dominate, was reserved but also exhibitionistic, and so on. There was an overwrought, hysterical quality to her thinness—if she was such a good cook, why didn’t she gain weight? Because “control, evidently, tasted better to her.”

Following Babitz’s cue, Anolik is especially needling when it comes to Didion’s marriage, which she finds both ridiculous and sinister. Dunne secretly had the hots for Babitz, but was also secretly gay. The evidence? Two gay friends claim that John seemed gay (one insisting, “He wouldn’t take his eyes off my crotch”). Anolik says that Dunne, who had a notoriously bad temper, secretly hit Didion, because she was what he pretended to be: successful. (Evidence of physical abuse? None.) “Soft-spoken, bird-boned Joan … was the real pro and little toughie,” leaving Dunne to “conceal how feeble” he was. “Scratch a bully, find a crybaby,” she taunts. What was Dunne crying over? “Exhaustion from all the caretaking Joan required” because playing the invalid was her favorite strategy—the migraines, and even an MS diagnosis, were all her trying to get ahead.

Anolik charges Joan with deliberately marrying an inferior, but who should she have married, Don DeLillo? She suspects that women writers who marry men who edit them (the two edited each other) are “marrying their writing,” thereby solving the inherent problem of being a woman writer—another career calculation. About the marriage becoming less fractious as they got older: “One of two things happened: Dunne’s anger mellowed or Dunne’s spirit was crushed.” About Didion remarking that the two grew dependent on each other later in life, Anolik weighs in: “A statement that warms the heart … or chills the blood.”

What can this possibly mean? Whose marriage could possibly pass muster? Anolik mentions her own husband in the book, a celebrity-endorsed cosmetic dermatologist, “the Michelangelo of Botox and Filler,” according to his website. I guess this counts as winning the husband Olympics compared to Didion’s poor showing. In an interview on Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop website about her skin care routine, Anolik speaks gratefully about him lasering her face twice a year, which doesn’t seem entirely different from being edited by your husband—or perhaps marrying your skin, per her conjugal balance sheet.

But, boy, does she have it in for Dunne, whom she accuses of being such a celebrity hound that if he’d been alive to attend Didion’s star-studded memorial service, he’d have had “drool leaking from every pore” trying to follow all the famous people around. This is a pretty ugly thing to say (and curious coming from a Vanity Fair writer). If the charge is celebrity transactionalism, then I’m confused about Anolik touting Goop eye cream in the Goop interview, and her husband being a “Goop Favorite,” and his dermatology practice a “best-in-class” on the site.

As to why Anolik is so vituperative about Didion’s marriage, I’m mystified. I only know that it renders her verdicts about anything even marriage-adjacent almost comically untrustworthy. You can definitely dislike Didion’s two late-in-life memoirs about the deaths of Dunne and their daughter, Quintana, but Anolik is positively savage. They’re false, self-serving, desecrating, a PR gambit—Joan may have felt grief about John’s death, but being alone was for her actually “a kind of fulfillment.” “Death, as it happened, suited Joan. She was so good at it,” Anolik writes. “She’d crawl over corpses to get to where she had to go,” and The Year of Magical Thinking was her “literally … crawling over the corpse of Dunne, crying all the while, but still crawling, still getting to where she had to go.” The result, we’re told, is that “America’s most compulsively self-referencing, self-fabulizing, self-consuming woman is able to transform herself into a national symbol of spousal grief. Our bereaved wife. Saint Joan.”

About the second memoir, Blue Nights, and her daughter’s death: Didion, whom Anolik alleges was secretly an alcoholic herself, “bequeathed” to Quintana the alcoholism that killed her, then spun it into publishing gold. I had thought we usually saved this level of moral contempt for the likes of an Idi Amin.

Then there’s the matter of Didion’s first lover, Noel Parmentel, whose name, Anolik makes a point of saying, she first came across in 2022, in a letter that Babitz wrote to her cousin. She’s breathlessly astonished at this discovery: A previous lover? “Say what and say who?”

What rings false is that even I knew about Parmentel, who’s quoted extensively in Tracy Daugherty’s 2015 biography of Didion, The Last Love Song, which Anolik has clearly read, because she later cites it. Treating Parmentel as a big discovery is like claiming to have invented the wheel while wagons are rolling up and down the street. Anolik’s new insight is that Parmentel was Didion’s “true” origin story, whose role in her life she disingenuously concealed.

Parmentel was a charmingly unreliable and womanizing journalist Didion met in New York when she was 22, just out of college, and writing for Vogue. He didn’t want to settle down, and they broke up. He introduced her to his friend Dunne, approved of them dating, and stayed with them regularly in California after they married. Didion, far from writing him out of her story, made him their daughter’s godfather.

In his nineties by the time Anolik tracked him down, Parmentel was still a dashing figure—indeed, she seems rather taken with him, sympathetically rapt as he unfurls the same grievances he’d aired to Daugherty: that the character of Warren Bogart in Didion’s 1977 novel, A Book of Common Prayer, was based on him, angering him enough to end his friendship with her. (Daugherty says it was the troublemaking Lewis Lapham who’d wound Parmentel up about the likeness, which Didion denied.) The irony is that Warren Bogart is an overbearing, bigoted, and abusive creep who thinks he’s charming but isn’t. If Parmentel saw a resemblance, it’s kind of a self-own.

Despite Parmentel saying things like, “Without me, there might never have been a Joan Didion. I invented Joan Didion” (he helped her get her first novel, Run River, published), Anolik obediently takes his side, sputtering about how awful Didion was for exploiting his friendship, then advances the dubious theory that she skewered Parmentel in her novel as an offering to Dunne, to appease his insecurities. Additionally: “Maybe there was for Joan something irresistible about the idea of giving herself to a man she didn’t love [Dunne] because the man she did love told her to. It was a chance to stoke the fires of her romantic masochism.” Anolik burrowing in Didion’s unconscious reminded me of the organ-invading creature in Alien—gruesome, inhumane, and unsubtle.

I did occasionally wonder if Anolik really meant all this seriously, since the writing itself is frequently overwrought to the point of absurdity. About a mutual friend of the two women named Earl McGrath: “Joan had her teeth sunk deep in his throat, was drinking, drinking, drinking with glassy-eyed, sweet-sucking bliss.” On discovering Eve’s letters: “I felt my mouth go dry, a queasy flutter in the pit of my stomach.… Fear and dread were beating in my blood along with my heart, a wet, heavy pump pump pump.” “Excitement rose in my throat like bile.” “My breath refused to catch, turn over. All I could do was breathe rapidly, shallowly, skimming off the top of my lungs.” That’s way too much about Anolik’s breathing.

Maybe the Harlequinesque hyperventilating is supposed to channel Babitz’s abandon, or perhaps punctuate her own role as romantic pursuer. Maybe it’s a rebellion against Didion’s famous restraint, but Didion could also be pretty stylistically annoying on occasion, and Anolik somehow lifts the worst of her mannerisms—the pileup of single-sentence paragraphs, the infernal word repetitions—then adds a lot of over-clever kickers and a stream of frantic exhortations to the Reader (“Now, I’m about to make a tricky point, so pay attention, Reader”), which got old for this reader after the first hundred times.

When she drops the frenzied stylistics, as when talking about Babitz’s sister, Mirandi, who spent decades as Eve’s caretaker-in-chief, the story becomes moving. The well-reported gossipy sections on the Los Angeles scene and its players in Babitz’s heyday are a pleasure. Her accounts of her grim in-person encounters with a “close to gaga” Eve are haunting. But more of the time the writing is forced and exhausting, like someone careening around at a party, yelling “Drink up!” in your ear, then barfing in a potted plant.

Babitz ended badly. A horrible freak accident—lighting a cigar in her car with a book of matches that somehow caught fire—left her covered with third degree burns that never entirely healed. She also had Huntington’s, a hereditary, debilitating illness. When Anolik met her, she was living alone with a soundtrack of right-wing talk radio (she turned Republican after 9/11, which alienated many of her remaining friends) and was literally delusional, fantasizing that she and Donald Trump were meeting for trysts at the Beverly Hills Hotel. A long-standing slob (one decades-ago ex described there being cat fur everywhere at Babitz’s place, even in the food), she was living in literal filth; Anolik was barely able to enter the apartment, the stench was so bad.

In Babitz’s account of the demise of her and Didion’s friendship, she’d been the one to end it after getting sober in 1982, because Joan was “too seductive.” She’d tried inviting Didion to an AA meeting with her; Didion said the rooms were too smoky. But is any of this true? Anolik takes her word for it, despite Babitz’s propensity for fabulation, and despite it seeming unlikely the two were in touch after 1973, when, as Anolik herself says, “mutual disenchantment set in.”

Nevertheless, Didion and Babitz ended up the same, she concludes: “the closest the other had to a secret twin or sharer,” both washed-up and fundamentally alone. Babitz had indeed stopped writing or socializing, but what was the evidence for Didion being washed-up? She was winning awards and getting career retrospectives. According to Anolik, those retrospectives were her being put out to pasture, “told that she’s both important and irrelevant.” Comes Anolik’s coup de grâce: “And I’m sure it’s killing her.”

Every era reinvents the biography form to suit its purposes, and there’s something very of the moment about this one. Call it the post-truth biography: Say anything, no matter how outlandish, maybe something will stick. It’s the sensibility of the Twitter mob: finger-pointing, salacious, malicious. I don’t have a problem resenting Didion for leading what seems to have been a mostly charmed life, for living at a time when Malibu beachfront property was affordable on a freelancer’s income, for her disproportionately allotted talents and photogenic looks. She was obviously ripe for a takedown, but there’s something awfully dispiriting about the moral space this one carves out.